# Calculate the probability of 5 heads in 10 flips

dbinom(5, # number of successes

size = 10, # number of trials

p = 0.5) # probability of success[1] 0.2460938For this lab or project, begin by:

R scriptAim to make the script a future reference for doing things in R!

In this lab we will use likelihood methods to estimate parameters and test hypotheses. Likelihood methods are especially useful when modeling data having a probability distribution other than the normal distribution (e.g., binomial, exponential, etc).

To estimate a parameter, we treat the data as given and vary the parameter to find that value for which the probability of obtaining the data is highest. This value is the maximum likelihood estimate of the parameter. The likelihood function is also used to obtain a likelihood-based confidence interval for the parameter. This confidence interval is a large-sample approximation, and may be inaccurate for small sample size, depending on the probability distribution of the data.

The log-likelihood ratio test can be used to compare the fits of two nested models to the same data. The “full” model fits the data using the maximum likelihood estimates for the parameter(s) of interest (for example, a proportion p). The “reduced” model constrains the parameter values to represent a null hypothesis (for example, that p = 0.5, or that p is equal between two treatments). The G statistic is calculated as twice the difference between the log-likelihoods of the two models (“full” minus “reduced”):

G <- 2 *(loglikefull - loglikereduced)

G is referred to as the deviance. Under the null hypothesis, G has an approximate χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference between the “full” and “reduced” models in the number of parameters estimated from data. We’ll work through an example below.

R commandsWe’ll start by getting familiar with the commands in R to calculate probabilities by answering the following:

# Calculate the probability of 5 heads in 10 flips

dbinom(5, # number of successes

size = 10, # number of trials

p = 0.5) # probability of success[1] 0.2460938# Calculate the probability of 10 boys in 20 births

dbinom(10, # number of successes

size = 20, # number of trials

p = 0.512) # probability of success[1] 0.1751848# Calculate the probability

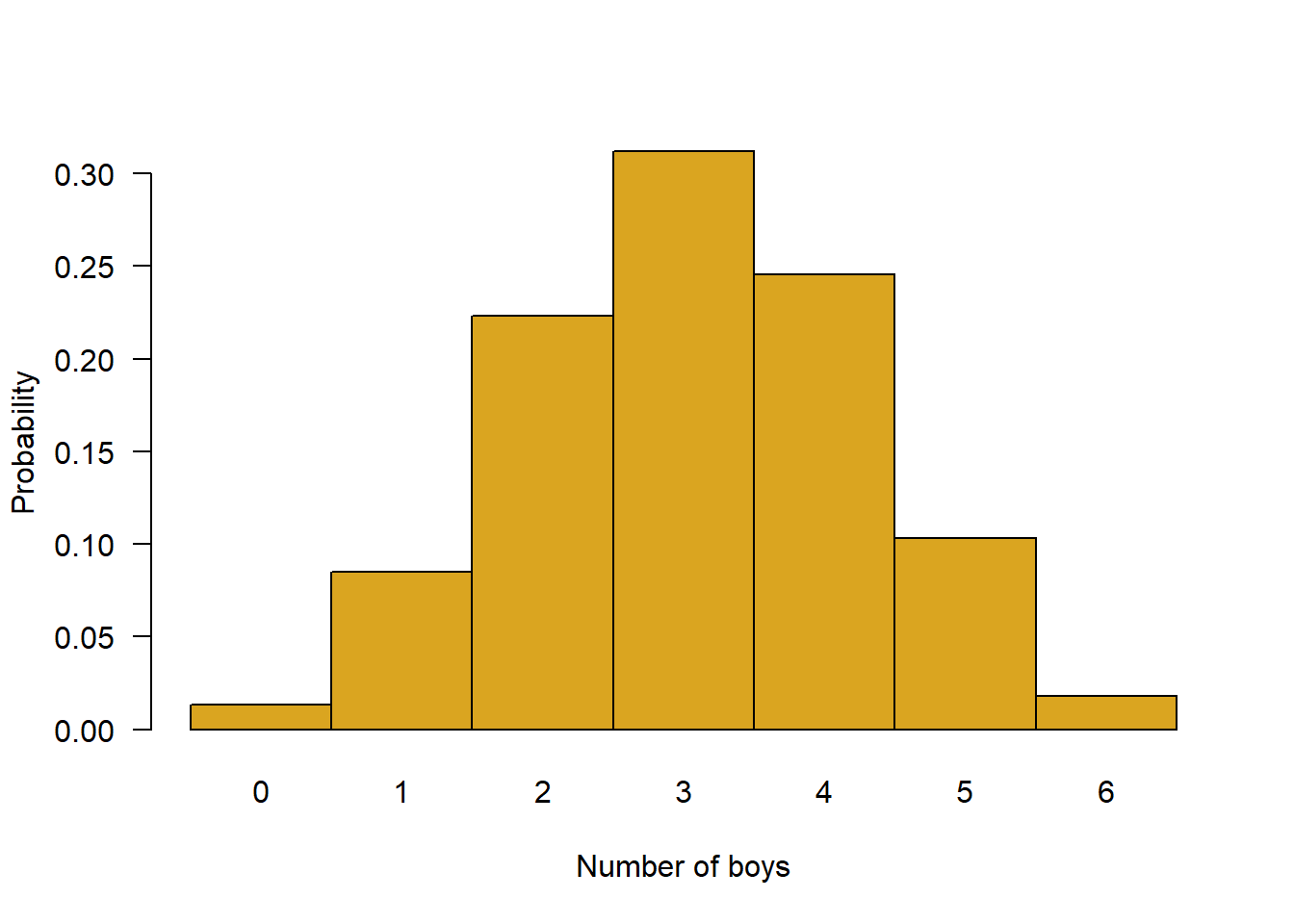

z <- dbinom(0:6, # number of successes

size = 6, # number of trials

p = 0.512) # probability of success

# Plot the probability distribution

names(z) <- as.character(0:6) # make the x-axis scale values

barplot(z, # data to plot

space = 0, # no space between bars

ylab = "Probability", # y-axis label

xlab = "Number of boys", # x-axis label

col = "goldenrod", # bar colour

las = 1) # rotate x-axis labels

geom()). X is any integer from 0 to infinity. If the probability of dying in any given year is 0.1, what fraction of individuals are expected to survive 10 years and then die in their 11th year?*# Calculate the probability

dgeom(10, 0.1)[1] 0.03486784# sum the probabilities of dying in years 0 through 5

sum(dgeom(0:5, 0.1)) [1] 0.468559# Calculate the probability

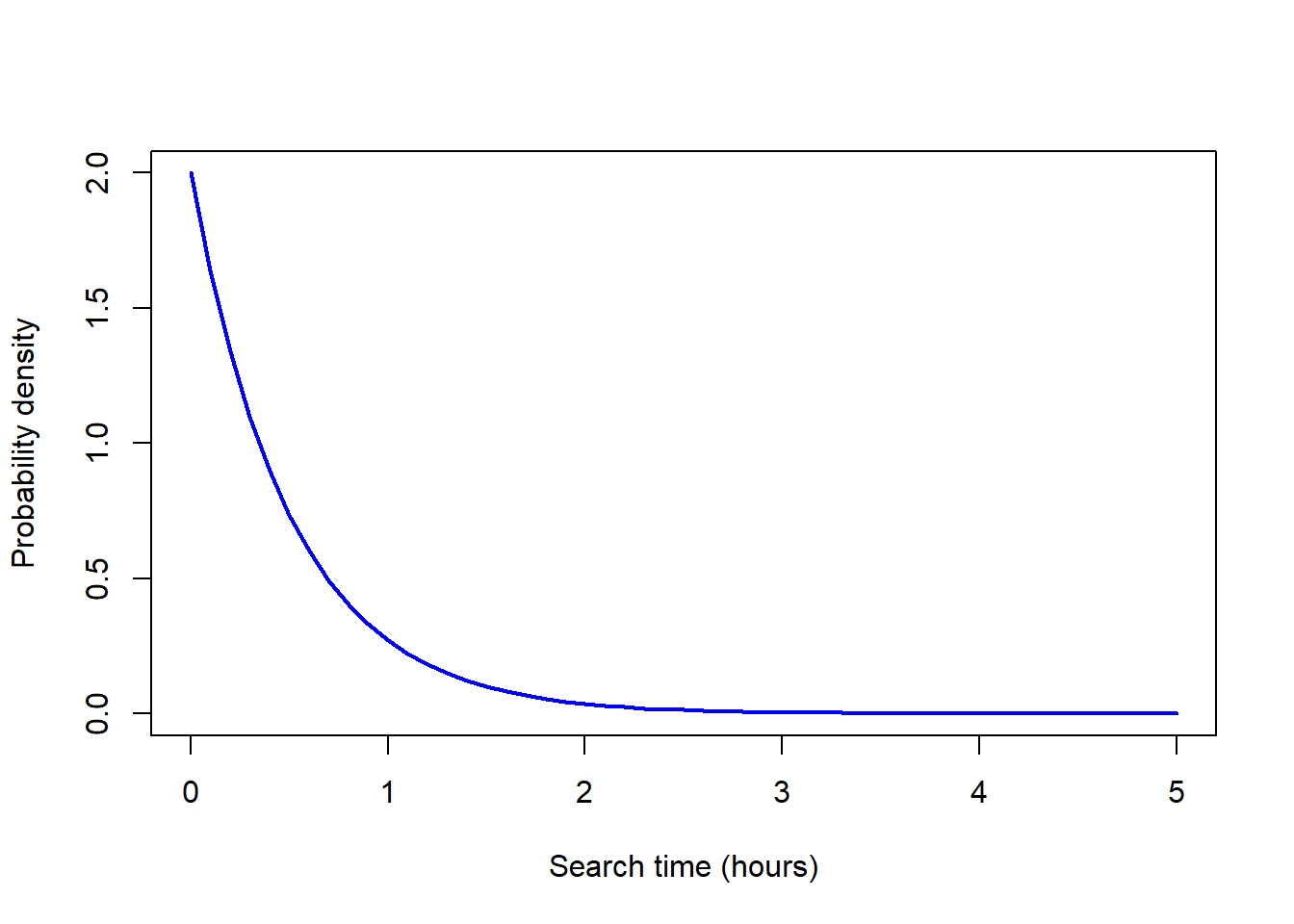

dexp(2, rate = 1/0.5)[1] 0.03663128# Make the x-axis scale values

x <- seq(0, 5, by = 0.1)

# Calculate the probability

y <- dexp(x, rate = 1/0.5)

# Plot the probability distribution

plot(y ~ x, type = "l",

xlab = "Search time (hours)",

ylab = "Probability density",

col = "blue", lwd = 2) # line colour and width

Individuals of most plant species are hermaphrodites (with both male and female sexual organs) and are therefore prone to inbreeding. The mud plantain, Heteranthera multiflora (a species of water hyacinth), has a simple mechanism to avoid such “selfing.” The style deflects to the left in some individuals and to the right in others. The anther is on the opposite side. Bees visiting a left-handed plant are dusted with pollen on their right side, which then is deposited on the styles of only right-handed plants visited later.

To investigate the genetics of this variation, Jesson and Barrett (2002) crossed pure strains of left- and right-handed flowers, yielding only right-handed F1 offspring, which were then crossed with one another. Six of the resulting F2 offspring were left-handed, and 21 were right-handed. The expectation under a simple model of inheritance would be that their F2 offspring should consist of left- and right-handed individuals in a 1:3 ratio (i.e., 1/4 of the plants should be left-handed), assuming simple genetic assortment of 2 alleles for 1 locus. You will explore this hypothesis by completing the following tasks:

1 - pchisq(G, df)

where df is the degrees of freedom, calculated as the difference between the two models in the number of parameters estimated from the data.

χ2 goodness of fit test? Analyse the same data using the chisq.test() command in R and comment on the outcome.library(tidyverse)

library(bbmle)

# 1. Generate a vector of p values

p_values <- seq(0.01, 0.99, by = 0.01)

# 2. Calculate log-likelihood for each p

log_likelihood <- function(p, n_left, n_right) {

n <- n_left + n_right

ll <- n_left * log(p) + n_right * log(1 - p)

return(ll)

}

n_left <- 6

n_right <- 21

ll_values <- sapply(p_values, log_likelihood, n_left, n_right)

# 3. Create a line plot

plot_data <- tibble(p = p_values, log_likelihood = ll_values)

ggplot(plot_data, aes(x = p, y = log_likelihood)) +

geom_line() +

labs(title = "Log-Likelihood Plot", x = "Proportion of Left-Handed Flowers (p)", y = "Log-Likelihood")

# 4. Narrow down the range for p

p_values_fine <- seq(0.05, 0.15, by = 0.001)

ll_values_fine <- sapply(p_values_fine, log_likelihood, n_left, n_right)

# 5. Determine MLE for p

mle_p <- p_values_fine[which.max(ll_values_fine)]

# 6. Likelihood-based 95% CI

# Define the profile likelihood function

profile_likelihood <- function(p) {

-2 * (log_likelihood(p, n_left, n_right) - log_likelihood(mle_p, n_left, n_right))

}

ci_bounds <- uniroot(profile_likelihood, c(0.094, mle_p))$root

ci_bounds <- c(ci_bounds, uniroot(profile_likelihood, c(mle_p, 0.400))$root)

# 7. Using bbmle package

mle_model <- mle2(minuslogl = function(p) -log_likelihood(p, n_left, n_right),

start = list(p = mle_p),

method = "L-BFGS-B",

lower = 0.01,

upper = 0.99)

summary(mle_model)

confint(mle_model)

# 8. Log-likelihood for MLE

ll_mle <- log_likelihood(mle_p, n_left, n_right)

# 9. Log-likelihood under null hypothesis

p_null <- 0.25

ll_null <- log_likelihood(p_null, n_left, n_right)

# 10. Log-likelihood ratio test

G <- 2 * (ll_mle - ll_null)

p_value <- 1 - pchisq(G, df = 1)

# 11. Chi-square goodness of fit test

chisq.test(c(6, 21), p = c(0.25, 0.75))The movement or dispersal distance of organisms is often modeled using the geometric distribution, assuming steps are discrete rather than continuous. For example, M. Sandell, J. Agrell, S. Erlinge, and J. Nelson (1991. Oecologia 86: 153-158) measured the distance separating the locations where individual voles, Microtus agrestis, were first trapped and the locations they were caught in a subsequent trapping period, in units of the number of home ranges.

The data for 145 male and female voles are in the file vole.csv. The variable “dispersal” indicates the distance moved (number of home ranges) from the location of first capture. If the geometric model is adequate, then Pr[X = 0 home ranges moved] = p Pr[X = 1 home ranges moved] = (1-p)p Pr[X = 2 home ranges moved] = (1-p)2p and so on. p is the probability of success (capture) at each distance from the location of the first capture. Use this data to complete the following tasks:

x <- read.csv("data/vole.csv",

stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

head(x)

# 1. Tabulate number of home ranges moved

table(x$dispersal)

# 2. MLE of p

p <- seq(0.05, 0.95, by = 0.001)

# Using for loop

# make a vector to store values we will calculate

loglike <- vector()

for(i in 1:length(p)){

loglike[i] <- sum(dgeom(x$dispersal, prob=p[i], log = TRUE) )

}

plot(p, loglike, type="l",

xlab="p", ylab="log likelihood",

col = "blue", lwd = 2)

# 3. MLE of p

max(loglike)

phat <- p[loglike == max(loglike)]

z <- p[loglike < max(loglike) - 1.92]

c( max(z[z < 0.858]), min(z[z > 0.858]) )

# 4. Expected numbers

frac <- dgeom(0:5, prob=phat)

round(frac,4)

expected <- frac * nrow(x)

round(expected, 2)

# Use the maximum likelihood estimate of p to calculate the

# predicted fraction of voles dispersing 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 home ranges.

frac <- dgeom(0:5, prob=phat)

round(frac,4)

# Expected distances moved

dist <- nrow(x) * frac

round(dist, 2)

# Compare with observed:

table(x$dispersal)The life span of individuals in a population are often approximated by an exponential distribution. To estimate the mortality rate of foraging honey bees, scientists have recorded the entire foraging life span of 33 individual worker bees in a local bee population in a natural setting. The 33 life spans (in hours) are in the file bees.csv. Use this data to complete the following tasks:

bees <- read.csv("data/bees.csv",

stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

head(bees)

# 1. Plot histogram

hist(bees$hours, right = FALSE, col = "goldenrod", prob = TRUE,

ylim = c(0,0.035), las = 1, breaks = 15)

# 2. MLE of rate (in per hour units)

rate <- seq(.001, .1, by=.001)

# Using for loop

loglike <- vector()

for(i in 1:length(rate)){

loglike[i] <- sum(dexp(bees$hours, rate = rate[i], log = TRUE))

}

plot(rate, loglike, type="l",

col = "blue", lwd = 2)

max(loglike)

mlrate <- rate[loglike==max(loglike)] # per hour

mlrate

# 3. Exponential might not be a great fit

hist(bees$hours, right = FALSE, col = "goldenrod", prob = TRUE,

ylim = c(0,0.035), las = 1, breaks = 15)

x <- bees$hours[order(bees$hours)]

y <- dexp(x, rate = 0.036)

lines(x, y, lwd=2)

# 4. 95% confidence interval

z <- rate[loglike < max(loglike) - 1.92]

c( max(z[z < mlrate]), min(z[z > mlrate]) )

# 5. Mean lifespan

1/mlrate

1/c( max(z[z < mlrate]), min(z[z > mlrate]) )